By: Brian Weidy

A provision dating back from the sixth century in Rome that has helped to keep bodies of water in Wisconsin free and available to the public is seeing one of its first contractions to the law in its more than 100 year history.

Buried deep inside the Wisconsin Constitution is the public trust doctrine, a series of protections for bodies of water in Wisconsin guaranteeing use by the general population.

Professor Arlen Christenson, a Professor Emeritus of Law and Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Law School as well as founding Board President of Midwest Environmental Advocates, lays out simply how the provision works.

“It holds that the state is the trustee of the waters of the state for the benefit of the people of the state,” Christenson said. “And so the trustee has a duty to care for, manage, improve and protect the water for the benefit of the citizens. It’s not as if the state owns the water, but the people are the beneficial owners of water, just as the beneficiaries of a trust.”

The Wisconsin Constitution states in article IX, section 1 that, “[T]he river Mississippi and the navigable waters leading into the Mississippi and St. Lawrence, and the carrying places between the same, shall be common highways and forever free, as well to the inhabitants of the state as to the citizens of the United States, without any tax, impost or duty therefor.”

Christenson would later go on to say, “The idea that as the doctrine evolved, it was read to protect a variety of rights of water including the right to recreate, to fish, to hunt game, to enjoy scenic beauty and to enjoy clean and healthy water.”

Ancient laws still hold today

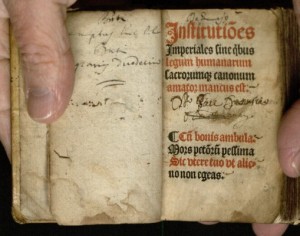

Public trust doctrines have a long history, both in the United States and well before that. In 530 A.D., the Roman Emperor Justinian and a group of lawyers wrote out for the first time Roman civil law called the “Institutes of Justinian.”

In this document, which covered nearly everything of or pertaining to Roman life, it stated, “By the law of nature these things are common to all mankind; the air, running water, the sea, and consequently the shores of the sea.”

From there, some version of the public trust doctrine has existed ever since in a number of legal documents throughout history. The Magna Carta featured a version of this to protect public water. The public trust doctrine was outlined in the Northwest Ordinance in 1787 in Article IV, which the Wisconsin Constitution more than 60 years later used word for word.

Setting a precedent

One landmark case in the history of the public trust doctrine occurred in 1972, Just v. Marinette County, where the Supreme Court ruled that the Just’s could not fill in the wetlands on their property because it sat on navigable waters.

This precedent setting case stated in the decision, “The changing of wetlands and swamps to the damage of the general public by upsetting the natural environment and the natural relationship is not a reasonable use of that land which is protected from police power regulation.”

“People who live on the shore or who own the shoreline of a navigable water, have certain rights but they don’t include the right to exclude people from the water,” Christenson said.

While Just v. Marinette set the precedent for wetlands, it was actually a case 60 years earlier that set much of the modern precedent for recreation on public lands.

In the fall of 1913, Paul Husting went hunting on Horicon Marsh, an area under control by a number of hunting clubs. On that day, he went to an area of the marsh controlled by the Diana Shooting Club. While staying on the original river channel, Husting was arrested for trespassing.

“But it was in public water, navigable water, so he raised the public trust [doctrine] as a defense,” Christenson said. “And the Supreme Court said he’s right that you can’t keep people out from hunting in navigable waters.”

This case set the precedent still used more than 100 years later when it comes to hunting on bodies of water in Wisconsin.

An exception to the law or a misinterpretation?

For more than a century, nearly all cases invoking the public trust doctrine in Wisconsin led to either an expansion or an affirmation of the section of the constitution.

“One of the things about the Wisconsin state court is that it has been pretty much an unbroken line of cases,” Christenson said. “No matter what the complexion of the Supreme Court is, of holding and expanding the public trust doctrine.”

This changed in 2013, when the state’s Supreme Court ruled in in the Rock-Koshkonong Lake District v. State Department of Natural Resources case that the public trust doctrine did not apply in this scenario because the wetlands were “non-navigable.”

The decision would later elaborate on that by stating, “If the public trust were extended to cover wetlands that are not navigable, it would create significant questions about ownership of and trespass on private land, and it would be difficult to cabin expansion of the state’s new constitutionally based jurisdiction over private land.”

Elizabeth Wheeler, a staff attorney at Clean Wisconsin, the oldest and largest state group dedicated to protecting Wisconsin’s environment, wrote an amicus brief on behalf of the organization in this case and believes the Supreme Court got this case slightly wrong.

“I think the Supreme Court was trying to distinguish whether the DNR could directly exercise their public trust responsibility on the impact to the wetlands,” Wheeler said. “Now in my opinion, the Supreme Court got it slightly wrong in the Koshkonong case because the wetlands directly in turn impact the water body….”

And the wetlands have a water quality and water quantity function in terms of how they interact with the lake there. And so I think they should have covered those particular wetlands under the public trust doctrine.”

Wheeler found that this was one of the first instances of the court not voting unanimously or voting to extend the definition of the public trust doctrine.

“Let me say this, the Koshkonong decision was the first time, to my knowledge, that the court limited the exercise or definition of public trust,” Wheeler said. “Until then, it had always been an extension and I think until then, it’s been … primarily unanimous decisions and Koshkonong was a split decision.”

Though he is worried about the precedent it might set, Christenson believes this is just a very small definition of the public trust doctrine and only impacts a very small portion of potential cases, which include isolated bodies of water that aren’t up to the prescribed height.

“The Just case … said that wetlands adjacent to or connected to navigable waters, stream or lake, were included in the public trust doctrine,” Christenson said. “The case you’re talking about [Koshkonong v. DNR] the question was whether it was an isolated or perched wetlands, which are not adjacent to navigable waters or connected to navigable waters are also protected by the public trust doctrine. And the court said no.”

Christenson would later add, “But that’s a pretty small case. If a court is hunting for a reason then it could possibly be extended, but I’d be surprised.”

A greater appreciation for water

Since its establishment as a state, the bodies of water in Wisconsin have played a huge role in the lives both recreationally and commercially for its residents. Christenson believes that this lengthy history of upholding and extending the public trust doctrine is just one of the ways in which the state shows its affinity for the state’s water.

“It reflects the reverence that most people in this state have for water,” Christenson said. “It’s just a part of our DNA that appreciates and wants to protect water in this state, the Great Lakes, the Mississippi, the streams we fish on and recreate on. It’s very important. And that gets to the Supreme Court, or at least it has for much of history.”