An increase in temperature has negative impacts on water resources in Madison, WI

By Liu Sitong

Wisconsin’s water resources, including lakes, streams, and groundwater, respond to climate in different ways. According to the historical records from the Wisconsin State Climatology Office, the average temperature in Wisconsin has risen between 1895 and 2013. This change in climate results in an increasing number and volume of floods, degradation of water quality, shorter periods of lake ice, and damage on ecosystems.

From 1895 to 2013, the annual temperature of the state of Wisconsin is gradually rising.

Source: Wisconsin State Climatology Office

“There’s no question that the Earth’s temperature is gradually increasing and many scientists refer this phenomenon to the greenhouse effect,” Kenneth Potter, professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said. “It’s true that the great amount of carbon dioxide is produced because of the population growth and the increasing of human activities.”

Potter’s research focuses mostly on the impact of climate change on precipitation (rain, snow, sleet, or hail that falls to the ground.) and flooding. He says that according to the precipitation patterns over the years, Wisconsin is receiving more floods and extreme rainfalls due to climate change.

From 1895 to 2013, the annual precipitation of Wisconsin shows an increase.

Source: Wisconsin State Climatology Office

“The air temperature is increasing because there’s more energy in the system, this causes the water cycle to move faster,” Eric Booth, the Assistant Research Scientist in the Departments of Agronomy and Civil & Environmental Engineering at UW-Madison, said. “Evaporation that requires energy speeds up, so the areas that typically receive rainfalls today are predicted to get even more rainfalls.”

In the Madison area, climate models predict the frequencies of heavier rainfalls in the future, according to the data from the Madison Airport Office. The report shows an increase in annual precipitation since 1930.

From 1870 to 2010, the number of days with 1.00 inches or more of precipitation is increasing.

Source: Wisconsin State Climatology Office

The Stormwater Working Group studies Wisconsin water resources and aims to improve the storm water management infrastructure. The group suggests that heavy flooding in Milwaukee in 2008 was partly caused by the heavier rainfalls. The Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts (WICCI) supports the group’s research.

More frequent floods resulting from intense rainfalls is a problem particularly for the urban areas. Because the vegetated soils are replaced with rooftops, streets, and parking lots, water cannot infiltrate through those surfaces.

“In Madison, there’s once a parking lot that received more than 5 inches of rainfall in a very short period of time on July 27th, 2006,” Booth recalled. The parking lot is between the police station and the bike path that’s near Camp Randall.

Lake flooding in Madison poses huge economic costs because it will damage homes and properties if reaches a certain level. Waves that are created by the motorboats will hit the shore. If the lakeshore goes under water, more areas will be damaged. It also affects people who love water skiing on the lake.

“The restriction on the use of motorboats is to minimize the damage on the lakeshore by limiting the speed of the motorboats from going too fast,” Booth said. “Several homes were flooded in the city of Monona in 2008 and there was this restriction for a month, people were not happy about that because they can’t go fast.”

Polluted water runoff is one of the biggest pollution problems in Wisconsin. According to Steve Vavrus, the Senior Scientist from the Nelson Institute Center for Climatic Research at UW-Madison, sediment and nutrients from the runoff can harm the state waters due to the increasing heavier rainfalls in size and quantity.

“The rainfall that turns into runoff along the surface will pick up contaminants as it moves down the hill and eventually hits the lake,” Booth said. “Water quality can become much worse following big storm events.”

When the polluted water reaches the lakes, it has a negative impact on the ecosystem.

“It will have huge impacts on the natural systems because some species cannot adapt to certain situations. ” Potter said.

Because the water either runs off or goes into the ground, water runoff pollution affects the quality of groundwater as well.

The majority of Madison’s water supply comes from groundwater. The city gets water from the deep aquifers, bodies of permeable rocks that allow a lot of water to move through them. Several hundreds feet below the ground, wells pump water out of the compressed sand.

“The water might be about 10,000 years old,” Booth said. “It is really clean and it’s lucky for Madison to have that.”

Not all of the groundwater is old and clean. The problem is that wells can be shortcuts for the polluted water to get into the aquifers. The soil closer to the ground surfaces, where the upper aquifers are located, may be more contaminated, so it mixes with polluted water that recently infiltrated.

“The upper aquifers respond more quickly to any contamination coming from the surface rather than the lower aquifers,” Booth said. “Luckily, there’ a layer in between the upper and lower aquifers that prevents water in the bottom layer from being contaminated.”

In Madison, less than 10% of the water supply comes from the aquifers in the upper layers.

The amount of time that ice covers Wisconsin lakes is also changing. It’s not clear if this is entirely caused by climate change but the shortening duration of ice covering shows consistency with increasing temperatures in Wisconsin.

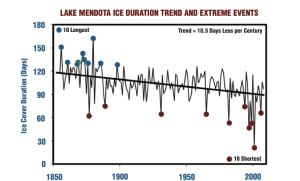

From 1850 to 2000, the ice duration of Lake Mondota declines gradually.

Source: Climate Wisconsin Project.

According to the Center For Limnology’s report, the longest ice cover durations on Lake Mendota in the past 150 years occurred before 1900. Since the 1980s, the number of days where ice covers state lakes has been reduced. The shortest ice cover durations are displayed more frequently after the 1980s. On average, there’s a reduction of 19 days per century in ice cover, according to the report.

Because ice cover occurs late and breaks up earlier, the amount of fishing on state lakes is limited. During the winter, there’re fewer days for ice fishing on state lakes. According to a report from the Climate Wisconsin Project that features stories on climate change, Lakes Mendota and Monona’s variation in temperature since 1855 suggested that in winter, temperatures could rise about 7-9 degrees Fahrenheit by 2055.

The rising water temperature also affects the rivers and streams in southwestern Wisconsin. According to the Coldwater Fish and Fisheries Working Group’s report, cold water fish can only live in an environment where the water temperature doesn’t go above 71.6 Fahrenheit. The fish species, particularly trout, will find it hard to survive if the streams get warmer.

The Coldwater Fish and Fisheries Working Group is another research group that has produced a report on the impact and adaptation to Wisconsin’s climate change under WICCI.

“Trout need cold water, but when the temperature is above 63 or 65 degrees, the fish start distressing,” Peter Cozad, a fly fishing guide in Viroqua, said.

Climate change impacts urban areas, such as Madison, more than rural areas. This is because of the Urban Heat Island Effect (UHI) that makes cities hotter than countries.

“In Madison, we are going to get more warmer days that are above 90 or even 100 degrees,” Potter said. “Plants cool themselves by losing water and the evaporations gives off temperatures, so it’s cooler in the rural areas than in the cities.”

The large amount of impervious surfaces, such as roads, parking lots, and driveways are absorbing and releasing more heat in the city.

“There are many surfaces such as streets and rooftops in urban areas that absorb a lot more heat than vegetation outside of the city,” Booth said. “The materials of those surfaces take radiation in, and release the sensible heat that can make temperature go up.”

The urban climate research team, under the Water Sustainability and Climate project (WSC), is looking for connections between heavily urbanized areas in Madison and potential risks for heat stresses by conducting multiple hospital visits.

“Global warming and the heat island effect work together changing the climate in Madison,” said Booth. “The heat island effect is more localized, though.”

———————————————————