By: Jenny Falk

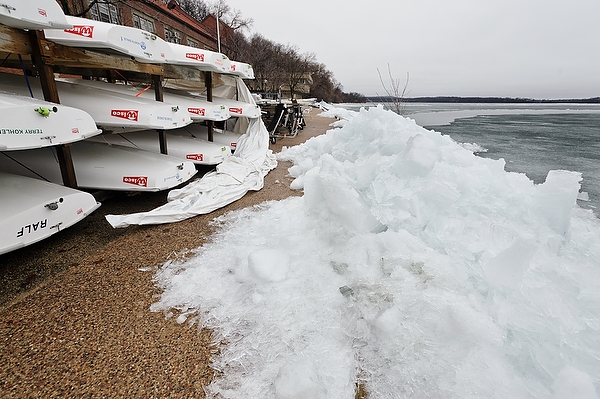

As the road salt comes out and the lakes freeze over, the water testing lab at Public Health Madison and Dane County puts the dust covers on the machines and settles in for a less busy season.

“It’s a lot quieter in here now than it is in the summer,” said public health’s lead microbiologist Jennifer Lavender Braun.

Lavender Braun heads the microbiology analysis coming in the lab doors. Virtually any water that Madison residents enjoy wallowing in during the summer months must be tested by Public Health Madison and Dane County. The department does water testing for all licensed swimming pools and whirlpools in the county and heads the program for monitoring the beaches during the summer.

The department heads a strong program for monitoring the county’s 16 beaches, making sure water is swimmable and safe for everyone, and making Dane County a front-runner in beach testing, according to Lavender Braun.

“There’s a lot of kind of mandated testing for a lot of the coastal beaches like on the oceans or Great Lakes, but for inland beaches, it’s not so much mandated and it’s really up to the local municipalities to decide what they’re going to do,” Lavender Braun said. “Dane County really has a strong program for their monitoring their inland beaches, considering that we’re getting around to 16 beaches a week.”

Summer can be a busy time for beach monitoring because the higher temperatures can increase the growth rate of bacteria, including the toxic cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae.

“We know that cyanobacteria blooms get worse as lakes get warmer. So warmer surface water is also going to contribute to bad water quality,” said Steve Carpenter, director of the UW Center for Limnology.

Algae off of a dock on Lakeshore Path. Source: Bryce Richter, University Communications Campus Photo Library

According to data from Public Health of Madison and Dane County, Dane County’s 16 beaches closed a total of 43 times in the summer of 2014. This is less than the average (since 1996) of 75 beach closures in a summer, according to an analysis by the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

“Just because we might have a few days when the water’s bad, it doesn’t mean it’s bad all the time. I think sometimes we get people who seem to think that the water’s just always bad. We have a lot of really good days at a lot of great beaches in the summer, and there are some bad days in there,” Lavender Braun said. “For the most part, even if it’s bad one place, we have so many beaches here that there’s probably a nice one somewhere in the county!”

Public Health Madison and Dane County sometimes works with other groups in the area for water monitoring, including the Clean Lakes Alliance.

The Clean Lakes Alliance tries to get citizens on board for water monitoring, hoping to correct some common misconceptions about our water quality. They head two programs intended to increase citizen participation in water quality monitoring. One is the “Adopt-A-Beach” program. In this project, with the help of citizen volunteers, the group sampled for E.coli Monday through Friday during the summer at James Madison Park. The samples they collected were then sent to the Public Health Department.

“They get sampling equipment from us and they bring the samples to us for the actual testing, but their staff goes out and does the sampling,” Lavender Braun said. “Then we report results back to them so that they can see if increased sampling finds additional beach closures that are missed with less frequent sampling.”

The Clean Lakes Alliance also leads an “End of Pier” program, when citizens wade out until they are knee or waist deep in water to check the water’s clarity, the intensity of waves, water temperature and other visual observations.

“What that program’s really trying to do is trying to locate and track the formation and movement of algal blooms and in particular, blue-green algal blooms because those are the ones that can have toxins that lead to beach closures,” said Katie Van Gheem, Watershed Engagement Coordinator with the Clean Lakes Alliance.

The “End-of-Pier” program saw 44 participants this past summer, a significant increase from summer 2013’s nine participants. In the summer of 2013, the program covered four of the five lakes in the Yahara River chain, but this past summer’s program included Lake Wingra as well.

“There are definitely some gaps we can try to target next year,” Van Gheem said. “There are definitely areas where we’re trying to target recruitment, especially on Lake Waubesa.”

Jon Standridge, a retired microbiologist from the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene, helps train citizen water monitors at the Clean Lakes Alliance. Standridge outlined a “three-prong approach” for getting citizens involved in the monitoring program.

First, he said you have to get them motivated. Then, it is important to get them to actually follow through and do testing. What’s important here is that citizens understand the “why” of what they are doing. To do this, the alliance gives lectures on phosphorous and its effect on the lakes, E.coli and water clarity. Finally, Standridge said you have to provide them with the equipment and show them how to use it.

“There’s a lot of chatter out there about the lakes being kind of crummy, so we’re trying to show them that’s not the case,” Standridge said.

Trainings include a couple of demonstrations using the equipment before having the citizen monitors try it for themselves. Also, citizen monitors are provided with picture examples to help them when classifying visual observations on a numerical scale.

“We have pictures of what we think represents each level, and so I think that helps volunteers go, ‘Oh, it looked like this today, OK,’” Van Gheem said. “It really helps them understand what we think it is to help them better understand it.”

Zoology student at UW-Madison Eric Krejcarek participated in the citizen monitoring program as part of a project for class. As a monitor, he did both “qualitative and quantitative observations” at three places on Lake Mendota. These observations included bather load, wave intensity, water fowl presence, plant debris, water and air temperature, as well as monthly phosphorous samples.

“I really like what [the Clean Lakes Alliance] is doing there. They really do care about the lakes and they’re vigilantly working to do what they can to help improve the quality of the Yahara watershed, especially Lake Mendota and Monona,” Krejcarek said. “It was an extreme pleasure working with them. They put a lot of work and hard effort into it, trying to get things running and trying to get community awareness because that’s one of the biggest things is getting support and awareness.”

“It’s a fun way to get out and spend time on the lakes. It’s easy to do. It’s not time intensive. And it’s a great way to get involved and learn about the lakes,” Van Gheem said.